The shining green tsavorite is a young gemstone with a very long geological history. Its home is the East-African bushland along the border between Kenya and Tanzania. The few mines lie in a uniquely beautiful landscape of arid grassland with bare, dry hills. It’s dangerous country, the habitat of snakes, and now and then a lion patrols, on the lookout for prey. There, near the world-famous Tsavo National Park, that history began.

The shining green tsavorite is a young gemstone with a very long geological history. Its home is the East-African bushland along the border between Kenya and Tanzania. The few mines lie in a uniquely beautiful landscape of arid grassland with bare, dry hills. It’s dangerous country, the habitat of snakes, and now and then a lion patrols, on the lookout for prey. There, near the world-famous Tsavo National Park, that history began.

In 1967 a British geologist by the name of Campbell R. Bridges was looking for gemstones in the mountains in the north-east of Tanzania. Suddenly he came across some strange, potato-like nodules of rock. It was like a fairy-tale: inside these strange objects he found some beautiful green grains and crystal fragments. A gemmological examination revealed that what he had discovered was green grossularite, a mineral belonging to the colourful gemstone group of the garnets, and one which had only been found on rare occasions until then. It was of an extraordinarily beautiful colour and good transparency. The find made the specialists sit up and take notice; Tiffany & Co. in New York also soon showed an interest in the newly discovered green jewel. However, in spite of all efforts, it was not, at the time, possible to export the stones from Tanzania. But Campbell Bridges was not one to give up easily. As a geologist, he knew that earth strata bearing gemstones were not necessarily limited to one particular area, indeed that they could extend over much greater areas – and in his opinion the stratum he had found was just such a one. For the rock belt in which most of East Africa’s gemstone mines lie is very ancient. It began to form many millions of years ago, while the continents were still very much on the move. At that time, the area concerned had actually been under the sea. The sedimental deposits between the continents were greatly compressed and folded as a result of the movement of the massifs. Through tremendous pressure and at high temperatures, the rocks which had been present originally were transformed. New, exciting, beautiful gemstones came into being – among them the tsavorite. Having said that, the tremendous forces of Nature damaged most of the crystals so badly at the time of their formation that today it is usually only grains or fragments which are found.

Campbell B. Bridges persevered. His surmise that the seam bearing the gemstones might possibly continue into Kenya finally put him on the right track. In 1971, he discovered the brilliant green gemstone for the second time, in Kenya. There, he was able to have the find registered officially and begin with the exploitation of the deposit. It was an adventurous business. To protect himself from wild animals, Bridges began by living in a tree-house. In order not to have any of the gemstones stolen, he set a python to watch over them, making use of the fact that his workers were afraid of snakes. It was a wonderful find. Unfortunately, the gemstone had been known only to specialists up to that point in time, but that changed quickly in 1974, when the Tiffany company began a broad promotion campaign which soon made the tsavorite well known in the USA. Further promotion campaigns followed in other countries, and soon the tsavorite was also known at international level.

Campbell B. Bridges persevered. His surmise that the seam bearing the gemstones might possibly continue into Kenya finally put him on the right track. In 1971, he discovered the brilliant green gemstone for the second time, in Kenya. There, he was able to have the find registered officially and begin with the exploitation of the deposit. It was an adventurous business. To protect himself from wild animals, Bridges began by living in a tree-house. In order not to have any of the gemstones stolen, he set a python to watch over them, making use of the fact that his workers were afraid of snakes. It was a wonderful find. Unfortunately, the gemstone had been known only to specialists up to that point in time, but that changed quickly in 1974, when the Tiffany company began a broad promotion campaign which soon made the tsavorite well known in the USA. Further promotion campaigns followed in other countries, and soon the tsavorite was also known at international level.

Green like a garnet …

So why is the stone called a tsavorite or tsavolite when it is actually a green grossularite and comes from the colourful gemstone family of the Garnet? The nomenclature of gemstones follows certain rules. According to modern mineralogical methods, gemstones are given a name which ends in ‘ite’. In honour of the Tsavo National Park, with its abundance of game, and the Tsavo River which flows through it, the former president of Tiffany & Co. Henry Platt, who had followed the developments of the gemstone from the very beginning, proposed the name ‘tsavorite’. Sometimes the term ‘tsavolite’ is used. However, both names denote the same stone, the latter version simply having the Greek suffix ‘-lite’ (stone).

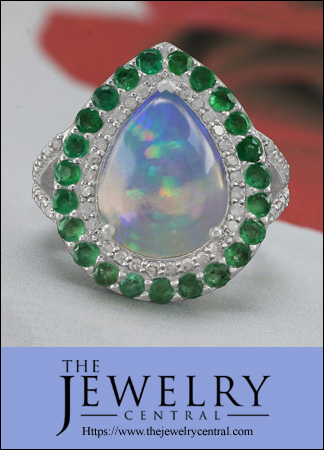

What is it that makes the tsavorite so desirable? Well, for one thing there is its vivid, radiant green. The colour range of the tsavorite includes a springlike light green, an intense blue-green and a deep forest green – colours which have a refreshing and invigorating effect on the senses. However, this gemstone is also valuable on account of its great brilliance. It has, like all the other garnets, a particularly high refractive index (1.734/44). Not without reason did they use to say in the old legends that a garnet was a difficult thing to hide. Its sparkling light was said to remain visible even through clothing.

Unlike many other gemstones, the tsavorite is neither burnt nor oiled. This gemstone is not in need of any such treatment. Like all the other garnets it is simply a piece of pure, unadulterated Nature. Another positive characteristic is its robustness. It has almost the same hardness as the (considerably more expensive) emerald, – approximately 7.5 on the Mohs scale – but it is markedly less sensitive. That is an important feature not only when it comes to the stone’s being set but also in its being worn. A tsavorite is not so likely to crack or splinter as a result of an incautious movement. It is well suited to the popular ‘invisible setting’, in which the stones are set close by one another, a technique which ought not to be used with the more sensitive emerald. Thanks to its great brilliance, the tsavorite is, in this respect, a partner to match the classics: diamond, ruby and sapphire.

Only in rare individual cases is a raw crystal of over 5 carats found, so a cut tsavorite of more than two carats is a rare and precious thing. But then that is one of the special features of this gemstone: that it can display its great luminosity even in small sizes.

There’s something very special about this young gemstone with the very long history. With its fresh, vivid green, its good wearing qualities, great brilliance and relatively reasonable prices, it is surely one of the most convincing and honest gemstones that exist.